[responsivevoice_button rate=”1″ pitch=”1.2″ volume=”0.8″ voice=”UK English Male” buttontext=”listen to this”]

by Thomas Linaras*, Greece

The dark light emitted by Werner Herzog’s work is only the blinding aura that crowns it.

This is not an oxymoron, since, from the very outset of his career, the German auteur has pursued, armed simply with his camera, the deeper truth of things that lies hiding in the heart of darkness. This meant – again, from the very outset – a constant and dangerous game of pushing the limits. A traveler in the true sense of the word, filming across the breadth and length of the planet Earth, Herzog has explored – with the passion and perseverance of a pioneer – the limits of the gaze, undermining the perceptive mechanisms of vision, burrowing like a miner into the tunnels of our existence, through uncharted regions of Being.

The ultimate goal of this 47-year-long peregrination all over the world is to capture and bring to the surface that which he refers to a the “ecstatic truth”: a way of stepping out of yourself and, having left the “burning ground of reality”, to land there again, carrying inside you the dimension of a revelatory experience. It is precisely in this risky cinematic act of trespassing the borders of the real and the limits of the cinematic medium that the visionary core of Herzog’s work lies. Accepting in advance that the essence and the truth of things remains out of sight is what motivates Herzog to pursue the primal image, the image of the first time, the unseen aspect of reality. His entire body of work is marked by the struggle and the striving to film the invisible, to reveal an uncontaminated, pristine image of nature and man.

Which is why even the most unsuspecting viewer is hypnotized, in a sense, by his images, which evoke the feeling of never before seen: whether it’s the old man on the island of Spinalonga who refuses to speak or the livestock auctioneers who talk a mile a minute; the woodcarver Steiner’s flight or the hot air balloon that flies above Guyana’s tropical forest; the hero of the film that hugs the tree or the televangelist; the raft adrift down the river or the ship going up the mountain; the pilgrims prostating themselves on the frozen lake or climbing Mount Kailash… And a necessary prerequisite for this to occur is for the river of real life to flow into the images and saturate the images indelibly, intertwining, almost magically, what occurs during the shooting (and plenty does occur) with the story being told in the film. Each of Herzog’s films bears the seal of its own spiritual fingerprint, the transmutation of real life into a cinematic act that is bigger than life, which, ultimately, is the higest decoration of his work.

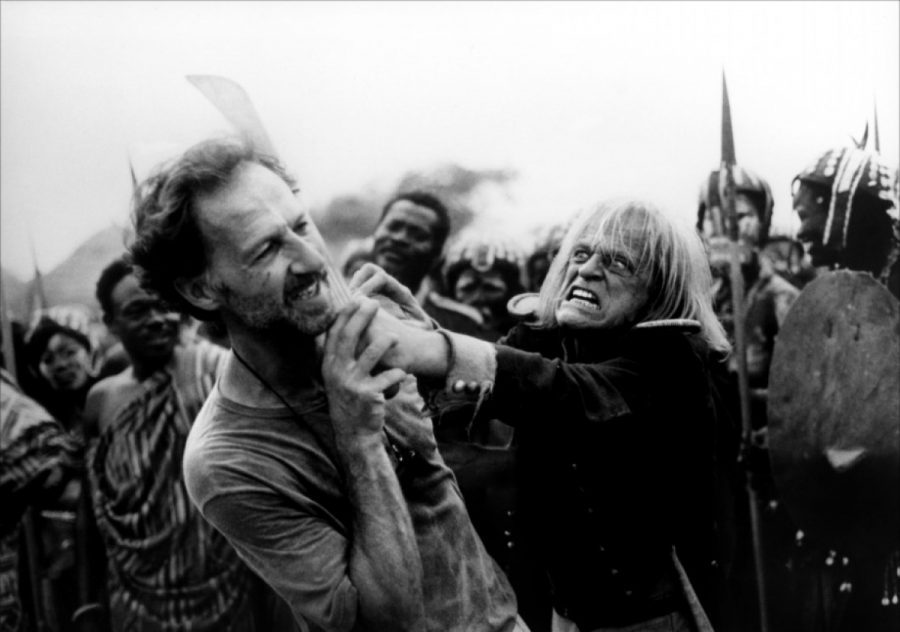

Herzog is not only a master storyteller, but a filmmaker that does not hesitate to fully adopt the gaze of his heroes, to truly stand in their shoes, since it’s his unshakable belief that that is the only way to understand and capture their truth and communicate it to us; even if it’s the gaze of a stray “alien” – because that is what Kaspar Hauser is, in essence – or the “bonafide” alien in The Wild Blue Yonder. Delving into the dark interiors of these heroes (“all my heroes come out of the night, they are walking shadows,” he says), Herzog palpates the tragic grandeur of defeat. Through these “weirdos”, these outcasts, these human “aberrations” that crowd his oeuvre (Woyzeck, Stroszek, Kaspar, Fini Straubinger, the dwarves, Nosferatu…), we are able to approach – Herzog seems to be telling us – our own enexplored limits, that unknown horizon of ourself, the existence of which we are not aware of.

Thus, reading his work along these lines, any attempt to classify it into fiction or documentary films is not only pointless, but also causes further confusion and misunderstanding. The pursuit of the “ecstatic truth” is a flight into the unknown, towards the outposts of existence, towards frontiers (cinematic ones too, needless to say) that are vague and mercurial, like the imperceptible yet perpetual movement of the desert sand dunes, in that place where everything bows down to the law of fata morgana: things are, and at the same time are not. The Sahara Desert, the Amazon jungle, the ridges of the Gasherbrum, Mount Kailash, the glaciers of the Antarctic, Kuwait’s flaming oil wells or the La Soufrière volcano – all these landscapes are real, and at the same time unreal; visionary lands penetrated by an intense metaphysical ambience. The way Herzog films nature is almost hallucinatory, it’s like looking at nature in a feverish state or as if you’re dreaming of it; while his landscapes look more like places of the imagination, lands that don’t exist outside of his images.

To what world belong the eschatological images of Lessons of Darkness, revealing a hell on earth – worthy of Hieronymus Bosch – of man’s own doing? To what time does Klaus Kinski belong, as, gramophone in hand, he lets Caruso’s divine voice spring forth and embrace the jungle, if not to the time of dreams? Is it a real or imaginary valley of windmills (an archetypical visionary image in Herzog’s work) that drives Stroszek mad in Signs of Life, Herzog’s first feature, filmed in Greece, on the island of Kos? What does Kaspar mean when he says “when I learn more words, I’ll understand that which I want to understand”, condensing, in this linguistic short circuit, Herzog’s exploration of the limits of language which, in his work, approaches the frontiers of silence?

Perhaps only the art of music – the only one it is worth turning the world into – and especially the music of absolute silence (in lands “where you can hear the beating of your heart”) is able, like a sword, to cut through the Gordian knot of language; To speak the words of the ineffable; to solve the enigma of images; to set free their hidden truth; to find the secret path that leads to the hearafter; to cross the deserted valley that lies between life and death.

And all this isn’t just theory, but arduous physical labor and it can only come about on foot, like the unequaled journey undertaken by the tireless German, walking for 21 days – from November 23rd to December 14th, 1974 – from Munich to Paris, in an act that broke through his limits – both physical and mental – in order to keep alive his friend, Lotte Eisner. (A true adventure of the soul, which was beautifully documented in his extraordinary book/travel journal, Of Walking in Ice).

Pursuing visions, reading signs and tracking the borderline, Werner Herzog has never stopped searching for the fleeting moment wherein lies nestled William Blake’s verse “to see a world in a grain of sand”.

*Thomas Linaras, Greek, studied Sociology at the University of Trento in Italy and worked for many years at the Thessaloniki International Film Festival as responsible curator of its publications. His critical essays on cinema and literature have appeared in various magazines. He lives in Thessaloniki. The text that thediagonales publishes is taken from his book “Tormenti Cinematografici, da Wim Wenders a Yasuhiro Ozu“, Edizioni Entefktirio, Thessaloniki, 2015.